If you are reading this, then the off-the-shelf Internet solutions for fun things to do when you’re bored, like Boredom Therapy and Bored Panda, probably have already failed you. Maybe you have tried searching the sub-genre of “what to do when you’re bored” on YouTube and it left you wanting more?

What you have landed on here … well … we are going to go a bit deeper.

My hope is that if you invest a little time to practice what I am putting down here, you will come away in the end with some long-term, self-reliant solutions for combating your boredom. Let’s get into it.

- Change Your Attitude: Boredom 1.0 vs Boredom 2.0

Our boredom is as natural as our hunger; boredom is going to happen to all of us from time to time. Most people don’t like being hungry; most people don’t like to be bored. Similar to how hunger is a signal we should eat manifested through a desire, boredom is a signal that we need to change our current situation manifested through a desire (Eastwood, Frischen, Fenske, & Smilek, 2012).

In casual conversation, boredom is generally thought of as bad. In psychology, though, it’s more of an ambivalent concept. Some researchers distinguish between “evolutionary” boredom and “contemporary” boredom:

- Evolutionary boredom (1.0): a biological opportunity for exploration and change

- Contemporary boredom (2.0): a state of disinterest and apathy

Tina Kendall, a lecturer at the Anglia Ruskin University in the United Kingdom, juxtaposes this modern, “complicit boredom of mass entertainment” with the type of boredom that was known by previous generations. Boredom 1.0 can be useful, existential and opens the door for creativity and self-discovery. Kendall cites the German philosopher Walter Benjamin who described boredom as a “warm grey fabric lined on the inside with the most lustrous and colorful of silks.” Similarly, Martin Heidegger considered boredom the “fundamental mood of philosophy, which attunes individuals to the ‘authentic’ nature of their existence in the world, by exposing them to a temporalized process of self-reflection.”

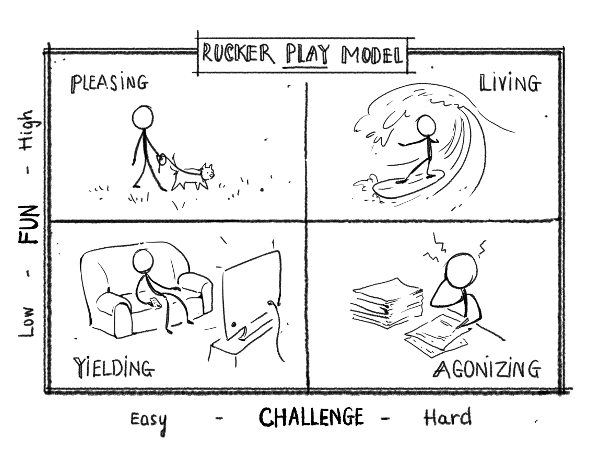

Some researchers more aptly call contemporary boredom, “shallow boredom” (Fisher, 2014). With all the modern opportunities today to learn, communicate and generate ideas, most of us have all the tools we need to avoid evolutionary boredom. However, this access has also brought with it a dark side, where avoiding boredom has progressed to escapism (represented in part by the Yielding quadrant of the PLAY Model).

Therefore, the first step in fighting modern boredom might be not to fight it at all but instead see it as it was meant to be, a signal for growth. Change your mindset and downgrade contemporary Boredom 2.0 back to existential Boredom 1.0, which can be a potentially productive and radical experience when used effectively.

- Improve Your Attention Span

Another thing boredom researchers have established is that there is a cognitive component to boredom. Some of might be highly motivated to escape boredom, but all our attempts fail. Why is that? According to recent studies, the problem could be our inability to stay attentive (Elhai et al., 2018; Hunter & Eastwood, 2018). A growing number of us are not able to keep our focus. When we lack focus, being bored is often a consequence.

Is this happening to you? Have you ever found yourself re-reading the same passage in a book because you couldn’t focus on it, or you wandered off during a conversation with your friends? Have you been playing with your kids and the desire to check your phone keeps interrupting what otherwise should be an opportunity for fun?

For some of us, myself included, staying focused is becoming more difficult. Individuals known to have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are the most at risk for experiencing boredom-like symptoms (Malkovsky et al., 2012).

When we don’t keep our attention in check, it is like being constantly interrupted by something or someone. Left unchecked, compromised focus leads to frustration and irritability. Andrew Hunter and John Eastwood, scientists from York University in Toronto, indicated we need to find ways to improve our ability to stay engaged and attentive to ward off boredom.

Two things that have helped me are meditative practice and eliminating the threat of distraction when I am with my kids by turning off my phone. The downside: I missed one important call. (Who cares?) The upside: I now have much deeper experiences with my kids.

- Engage in Positive Daydreaming

Daydreaming temporarily takes us away from our current reality, bored or otherwise. Almost 40 years ago, research by Richard Smith showed that when workers are bored, they use daydreaming as a coping strategy (Smith, 1981). While acknowledging that daydreaming can be detrimental (e.g., guilt and fear of failure daydreams), daydreaming also has a ton of positive potential. One constructive way to beat boredom is adopting a positive-constructive daydreaming style (Dauphin & Heller, 2010).

Dr. Jerome Singer (1975) introduced the idea of positive daydreaming. Positive daydreaming is characterized by enjoyment and positive anticipation. When we daydream in this way, it can help us with problem-solving, and it increases our creativity and releases tension. As long as daydreaming is not used as escapism, it is an amazing occasional antidote to boredom (especially because it can point the way to new adventures). It also leads to better outcomes than other popular alternative strategies people use to alleviate boredom, like emotional eating, impulsive shopping, and other addictive behaviors (Dal Mas & Wittmann, 2017).

- Find the Optimal Level of Arousal

We still don’t know if boredom is a state of low arousal, high arousal or both. While some scientists see boredom as similar to a physiological state of sleep, others connect it with restlessness and being “fidgety” (Danckert et al., 2018). Regardless of which scientific camp is right, the key to fighting boredom might be to find the optimal level of arousal for you.

For some of you, fighting boredom may be about finding activities and places that reduce stress, offer relaxation and provide you with the space to explore your feelings and self-reflect (i.e., Boredom 1.0). For others, it may be about looking for new friends and opening yourself to new experiences. Unfortunately, I cannot provide a one-size-fits-all answer; it’s more about learning what works for you and following your gut to find the right balance.

For my truly introverted friends, research by Dr. Louis Leung (2015), a professor at the School of Journalism and Communication in Hong Kong, suggests that for some solitary activities and alone time can bring the state of optimal arousal. Leung discusses the positive dimensions of aloneness and solo activities and how they can lower the arousal levels for some people (who might be over-stimulated).

Boredom and the PLAY Model

When boredom is associated with low arousal (i.e., having too much time on our hands), we may benefit from Living activities (see: PLAY Model); for most of us, though, the pursuit of optimal arousal will involve finding Pleasing activities from the PLAY model.

- Engage in Satisfying Activities

Finally, let’s review the scientific definition of all types of boredom: an unfulfilled desire to be engaged in a satisfying activity. One thing gets right to the heart of the problem of boredom: identifying and engaging in satisfying activities. To do that, let’s look at the PLAY Model one last time. Boredom-killing activities are found in the Living quadrant (high fun-high challenge activities) and the Pleasing quadrant (high fun-low challenge).

The aim is to discover and implement these types of activities in your life and prioritize them. Do this and you will never have to Google fun things to do when you’re bored again.

Sources & further reading:

Dal Mas, D. E., & Wittmann, B. C. (2017). Avoiding boredom: Caudate and insula activity reflects boredom-elicited purchase bias. Cortex, 92, 57–69.

Elhai, J. D., Vasquez, J. K., Levine, J. C., Lustgarten, S. D., & Hall, B. J.(2018). Proneness to boredom mediates relationships between problematic smartphone use with depression and anxiety severity.Social Science Computer Review, 36(6), 707–720.

Danckert J., Hammerschmidt T., Marty-Dugas J., Smilek D. (2018). Boredom: Under-aroused and restless. Consciousness and Cognition. 61:24-37.

Dauphin, B., & Heller, G. (2010). Going to other worlds: The relationships between videogaming, psychological absorption, and daydreaming styles. CyberPsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, 13(2), 169.

Eastwood, J. D., Frischen, A., Fenske, M. J., & Smilek, D. (2012). The unengaged mind: defining boredom in terms of attention.Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(5), 482–495.

Fisher, M. (2014). No one is bored, everything is boring. Visual Artists Ireland, https://visualartists.ie/articles/mark-fisher-one-bored-everything-boring.

Gaston, A., Moore, S., & Butler, L. (2016). Sitting on a stability ball improves attention span and reduces anxious/depressive symptomatology among grade 2 students: A prospective case-control field experiment. International Journal of Educational Research, 77, 136–142.

Hunter, A., & Eastwood, J. D. (2018). Does state boredom cause failures of attention? Examining the relations between trait boredom, state boredom, and sustained attention. Experimental Brain Research, 236(9), 2483-2492.

Hunter, J. A., Abraham, E. H., Hunter, A. G., Goldberg, L. C., & Eastwood, J. D. (2016). Personality and boredom proneness in the prediction of creativity and curiosity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 22, 48–57

Kendall, T. (2018). “#BOREDWITHMEG”: Gendered boredom and networked media. New Formations, 93, 80-100.

Leung, L. (2015). Using tablet in solitude for stress reduction: An examination of desire for aloneness, leisure boredom, tablet activities, and location of use. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 382–391.

Malkovsky, E., Merrifield, C., Goldberg, Y., &Danckert, J. (2012). Exploring the relationship between boredom and sustained attention. Experimental Brain Research, 221(1), 59–67

Singer J.L. (1975). The inner world of daydreaming. New York: Harper & Row.

Smith, R. P. (1981). Boredom: a review. Human Factors, 23(3), 329–340.