Even in the familiar, there can be surprise and wonder. —Tierney Gearon

Imagine you’re dead asleep. You got to bed a little late the night before, so your REM cycle is delayed a little later than usual. You’re blissfully dreaming (unaware that you should be up already) and then: cue LOUD music. Startled, you jolt up … only to see your significant other serenading you with a ridiculous song.

View this post on Instagram

What do you feel?

First of all, welcome to life as musician YX’s girlfriend. Secondly, you may start out annoyed—but wouldn’t you love it a little bit, too?

I would venture the majority of us would develop an enduring memory of this silly surprise, as it’s generally exciting when something happens we don’t expect. Even if we have basic expectations for something (but perhaps aren’t quite sure of the details), we wonder if what awaits us will be pleasant or unpleasant. This kind of wonderment stimulates us.

We do know, though, according to science, it’s a little bit more complicated than that (see section: For the (surprise) haters). Love or hate them; surprises are an interesting phenomenon that profoundly affects our neurology and psychology, highlighting our humanity.

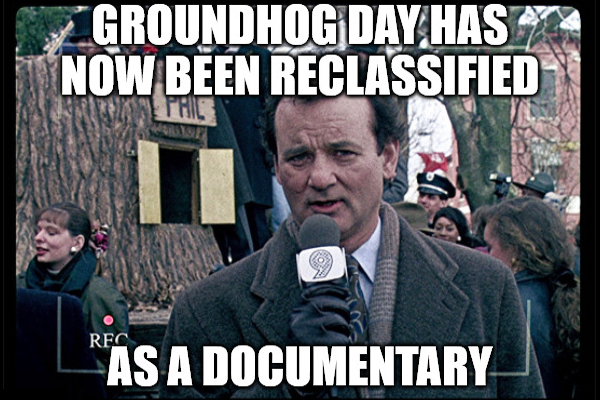

As we collectively make our way through the era of COVID, with many of us feeling like we are living through the extended edition of Groundhog Day, the prospects of getting excited by a surprise are bleak.

But even during a lockdown, surprise can be a way to break the boredom that comes with monotony.

What does surprise mean?

So, what does surprise mean? Are surprises always eventually good? Can we have conflicting emotions about them?

Let’s dive in:

Simply, a surprise means that we receive unexpected stimuli interrupting our ongoing thoughts and activities. It disturbs the coherence and predictability of our reality and, because of the disruption, it takes time for us to process. Once we’ve processed the surprise, we either become happy (with a positive surprise) or disappointed/scared (with a negative one).

Further, Drs. Marret K. Noordewier and Eric van Dijk from the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences at Leiden University in the Netherlands posit the need to distinguish between initial and later response to the surprise, which might not match. For instance, even if the surprise is a good one, the initial reaction can be a bit negative because most of us don’t like our world’s structure to be suddenly broken.

In their article, published in the journal Cognition and Emotion, Noordewier and van Dijk write that “even if the surprising stimulus is positive, people first experience this brief phase of interruption and surprise, before they can appreciate and welcome the outcome as it is.” Our responses to surprise are, therefore, quite dynamic, and our initial reaction is not always the same as our subsequent response. So while YX’s girlfriend initially reacted by throwing her pillow at him, her response transitioned to one of mirthful annoyance once she understood what was happening.

The appeal of the unexpected

It’s also important to note surprises can be more subtle than a loudspeaker violently extracting us from our dreams. Often, we may not even realize the pleasurable role the unexpected plays in our day-to-day lives.

A study conducted by a research group from the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, shows that we are indeed drawn to the unexpected element of surprise. Surprises often increase our pleasure in a given moment. This is because our nucleus accumbens—a region in the brain associated with pleasure and reward expectation—responds most strongly to unexpected events (e.g., receiving a gift when it’s not your birthday).

In this experiment led by Drs. Gregory S. Berns and Read Montague (both of whom are medical doctors), 25 participants each had fruit juice or water squirted into their mouth in a pattern that was either fixed every 10 seconds or unpredictable. During the experiment, the volunteers underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to show brain activity. The resulting data indicated there was a rush of dopamine—a neurotransmitter that plays a major role in reward, pleasure, motivation, memory, and attention—when the juice or water was dispensed at unpredictable intervals. In fact, the event’s unpredictability played a more significant role than whether a participant liked or disliked the fluids. This led the team to conclude that our reward pathways become more strongly activated by the unexpectedness of the stimuli than by how much we actually enjoy the stimuli’s effect.

The finding of this study is somewhat logical from an evolutionary perspective. Our brain is wired to pick up change, which takes precedence over other stimuli (e.g., pleasure) because sudden change can be a signal we need to react to something dangerous quickly. Fortunately, many of the dangers that evolution prepared us for are gone. Although bad surprising things still happen, the days a saber-toothed tiger jumping out at you are long gone. Nowadays, even unpleasant surprises are events we can reframe and have a laugh after we’ve made it through them. For instance, if you’ve ever taken a swig of a drink expecting it to be water, but it’s something else—doesn’t your brain do a double-take? And while at first, it can be weird and confusing, incidents like this usually end being somewhat humorous in the end.

For the (surprise) haters

Alright, at this point, it’s important to acknowledge those among us who genuinely hate surprises. We know you exist, and you are just as deserving of fun as surprise-lovers. To you, the idea of a surprise pre-work serenade sounds awful. I suspect your reaction to YX’s serenade would be something like, “Does this person know me AT ALL?!” and likely stays that way even after you’ve processed the surprise.

A study published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin reported on an experiment in which participants were shown different images and asked to come up with innovative names for a new type of pasta. One group was shown photos that somewhat “broke the mold” (e.g., an Eskimo in the desert), and the others were given images that depicted scenes you would expect to see (e.g., an Eskimo in the snow). Perhaps unsurprisingly, the group showed unexpected images later came up with more original answers than participants that viewed the non-surprising images.

Here’s the catch, though: the surprise element only inspired those participants who had a low need for structure—their divergent thinking was enhanced by the unpredictability of the images they had been shown. In contrast, those with a high need for structure experienced a decrease in divergent thinking when presented with incongruous photos, suggesting surprises don’t necessarily work for everyone.

Don’t forget that finding: having fun means knowing what does (and doesn’t) work for you.

Integrating the unexpected in the pursuit of fun

While many of us might be drawn to surprise and unpredictability, we cannot expect to be given a constant stream of surprises to activate our pleasure centers. However, let’s discuss how we can sustainably use the unexpected to create more fun and pleasure in our daily lives.

For example, Vincent Cheung of Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences and his colleagues found a simple way we can engage in the pleasure of surprise is by indulging in our favorite music. In their study, they analyzed 80,000 chords in US Billboard pop songs. They found that the best ones (the ones producing feelings of pleasure in listeners, as measured by an fMRI) included a balance of surprise and unpredictability. When listeners were surprised by a chord that deviated from their initial expectations, they experienced more pleasure than when the music matched their anticipation.

Additionally, in my interview with Alexandre Mandryka about peak experiences, the two of us discussed the relationship between uncertainty, the creative process, and having more fun. According to Mandryka, complexity in execution and the opportunity for varied results increase the possibility for fun, making the unexpected a key component in achieving fun.

What does surprise mean in your day-to-day?

How do you find surprises in your everyday life? If you feel like your daily routine is stuck on repeat, maybe it’s time to casually inject some opportunities for the unexpected into your life. You may find yourself pleasantly surprised. The kids and I find some relief from the lack of opportunities for surprise through games.

What’s your favorite type of surprise? Or better yet, your favorite way to surprise? Please let me know in the comment section below.

Sources & Further Reading

Berns, G. S., Pagnoni, G., McClure, S. M., & Montague, P. R. (2001). Predictability modulates human brain response to reward. Journal of Neuroscience, 21(8), 2793–2798.

Cheung, V. K. M., Koelsch, S., Harrison, P. M. C., Pearce, M. T., Meyer, L., & Haynes, J.-D. (2019). Uncertainty and Surprise Jointly Predict Musical Pleasure and Amygdala, Hippocampus, and Auditory Cortex Activity. Current Biology, 29(23), 4084–4092.e4.

Gocłowska, M. A., Baas, M., de Dreu, C. K. W., & Crisp, R. J. (2014). Whether Social Schema Violations Help or Hurt Creativity Depends on Need for Structure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(8), 959–971.

Meyer, W. U., Reisenzein, R., & Schützwohl, A. (1997). Towards a process analysis of emotions: The case of surprise. Motivation and Emotion, 21, 251–274.

Noordewier, M. K., & van Dijk, E. (2019). Surprise: unfolding of facial expressions. Cognition & Emotion, 33(5), 915–930Rucker, M. (2020, September 16).

Interview with Alexandre Mandryka about Peak Experiences. MichaelRucker.com: Thought Leader Interviews. Retrieved from https://michaelrucker.com/thought-leader-interviews/alexandre-mandryka-peak-experiences