Professor, researcher and stand-up comedian are all great descriptors of Dr. Ryan Hamilton. Ryan is an Associate Professor of Marketing at Emory University’s Goizueta Business School, where he has taught since 2008. Led by a desire to know how people make decisions, he studied marketing at Northwestern after studying physics and deciding along the way that it was not something he could spend his life focused on. Ryan has consulted with, or done speaking engagements for, a large portfolio of businesses, including Home Depot, Walmart, and Johnson & Johnson. He has also been published in numerous peer-reviewed journals and continues researching and writing about his findings. One of his favorite parts of being a dad of five young kids is being able to play with Legos and watch SpongeBob SquarePants. Giving presentations isn’t the only time Ryan has taken to a stage; as mentioned above, he also has experience writing and performing stand-up comedy.

1) The standout reason I knew I wanted to learn more from you was when, while discussing how to build healthy habits, you quoted Terry Crews saying, “…as long as you’re having fun, you continue to do it.” Why is “having fun” important to architecting desirable habits?

Terry Crews, American treasure! For people unfamiliar with Terry, he’s an actor, former athlete, and in fantastic shape. Accordingly, he gets a lot of people asking him how they can stay in shape, and he gives fantastic advice: it needs to be fun!

The reason that it needs to be fun is that the part of our mind that is responsible for the formation and reinforcement of habits—and then the activating of habits once they’re formed—is this automatic intuitive part of our brain. It responds to fun cues. So, for example, if you’re thinking about an exercise habit, a lot of the rewards of an exercise habit for many of us—not for all of us, but for many of us—a lot of those rewards are long-term goals. For example, I’m going to look great for swimsuit season, or I want to stave off heart disease.

Unfortunately, the parts of our mind that resonate with these kinds of long-term rewards are not the ones in control of habit formation. So, if we want to engage those parts of the mind, it needs to be a more immediate reward. This is part of the reason why it is so much easier to form bad habits than good habits, because bad habits are fun. They reward that automatic part of our brain.

Terry Crews’ advice for people is, if you want to go to the gym, make the gym fun. In fact, he says go to the gym and just read a magazine. Just make the goal going, because if you can make going to the gym fun, then you can likely start to ramp up the pain a little bit over time. You’ll have already formed the habit of going, and that’s the big hurdle. So, Terry Crews, in addition to all the amazing other things that he does, he also dispenses great psychological advice.

2) If a System 1 “reward” is essential to creating a lasting habit, what are some key considerations for getting this right? For instance, it’s common for people to think that the equity of disciplined labor is a suitable reward, but it appears clear from science this isn’t necessarily true. In fact, multiple researchers in the field have told me the opposite is likely true.

The System 1 and System 2 distinction is System 1 is automatic and quick, essentially effortless, requiring no sense of voluntary control. Where System 2 requires our attention. It requires effort and requires mental activities.

I honestly think that it’s been a little over-applied. It’s been force-fitted into too many things for which it’s not a natural explanation. But for me, it was really powerful in helping to understand goals when I made the connection. I don’t claim to be the first to make it, but when it was made for me, I saw its application regarding habits. It helps us stop pretending that we can entice our habit system by simply having great goals. System 1 is an automatic system and enjoys immediate rewards. If we want to form good goals, we need a language that takes these short-term rewards into account—and having fun is a major one. Making things easy tends to be a good reinforcer of this automatic system. When we figure this out, then we can kind of “hack” the habit matrix. We can start to pair good habits with System 1 rewards, which end up being much more effective than System 2 rewards.

3) You’ve stated, “a lot of what we do is driven by an impulse for consistency.” In my work, I’ve found that once I get people to actually have fun—consistently—the rest tends to become rather easy. However, breaking the initial inertia is a heavy lift. Furthermore, a lot of motivational rhetoric (juxtaposed with tactics of action) leads to guilt, dissonance, and further resistance rather than change. Taking all this into account, when desired, how do we achieve a “new” consistency as smoothly as possible?

You ask such easy questions. So, the short answer is, we don’t. I should start with a small caveat, which is that a lot of our behaviors are driven by consistency. I also want to clarify that this is my opinion, and not based on a lot of specific empirical support. Instead, it is my broad view based on the available literature. Still, I do believe that a lot of what we do is wanting to see ourselves as consistent with who we were in the past, and wanting our behaviors to be consistent with our beliefs, and so on. So, in terms of why it’s a problem (before we get into what to do about it), the reason it is often difficult to change to a new consistency state is that we have to change so many things simultaneously, right? For example, if we don’t see ourselves as a fun individual, then trying to have more fun in our lives—that might feel inconsistent. And, so, we want to snap back to that initial self-perception.

Suppose we want to change our perception, to be more of a fun person. Well, now we’ve got all this evidence from our behavioral past that we’re not fun, making things hard to change. Another example is if we don’t see ourselves as athletic or healthy, then going to the gym feels inconsistent with the way we’ve seen ourselves previously. This highlights why it isn’t easy. It’s because you have to change so many things at once, and then you have to stick with the new habit long enough to update all of those behaviors, update all of those beliefs, update your self-perception, and then over time, carve a groove of new consistency.

In terms of how to do it as smoothly as possible, my opinion (based on not a lot of great evidence) is that the self-perception component might have more power than behaviors and beliefs. So, we think about behaviors, beliefs, and self-perception. For instance, if I can somehow convince you that you are an athlete, then that will, on the margins, make it easier for you to update your beliefs to be consistent with that idea, as well as update your behavior to be consistent with that idea. I think a lot of us lead with beliefs or behavior, and that can still work. If you force yourself to go to the gym long enough, then eventually you’ll start to see yourself as somebody that goes to the gym, you’ll see yourself as a healthy person, but if I can convince you you’re already an athlete, it becomes easier. Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman did a good job of that with his assertion, “if you have a body, you are an athlete.”

So, in your work, helping to convince someone they’re “fun” or enabling them to consider themselves as a fun person, to have them incorporate that perception, I think there’s power there. Again, this is not based on any data. It’s my intuition, that if we can change our self-perception, then our beliefs and behavior will be easier to follow through on, rather than starting with behavior or beliefs.

4) You teach a business course on humor in the workplace. First off, amazing! What are the documented (potential) benefits of humor that make this worthy of teaching?

First, I recommend the book Humor, Seriously by Jennifer Aaker and Naomi Bagdonas. It’s a great text on humor. When I teach humor, I divide the benefits of humor into four categories, which I call: reprieve, affinity, creativity, and rhetoric.

Reprieve is humor that can relax us. It gives us a break; it eases tension. Through laughing, which is a kind of a social lubricant, it can give us a sense of affinity that bonds us. It is a way of easing tension. Somebody says something awkward, and we all kind of laugh, and that’s because humor can serve this function. It becomes this learned behavior of signaling. When we laugh together, it bonds us and brings us closer together. It releases oxytocin. There’s evidence showing that when we engage in humor, it breaks down traditional ways of thinking, breaks down barriers, and promotes creativity. This is because a lot of humor is sideways thinking; it’s about making disparate connections and then making them make sense.

Humor can also be a rhetorically powerful tool. For this, I teach Aristotle’s rhetorical triangle, which is ethos, pathos, and logos. Pathos is the evaluation of the audience: if we are humorous, then that can bond people to us. Ethos is the evaluation of the speaker: evaluation of messages and logos. Humor can drive attention. It can improve memory regarding what we remember.

Then, I map into this lecture the implications for leadership, the benefits for relationships, and the benefits for mental health and physical health. I do have whopping huge warnings though about the type of humor we engage in. There’s research on humor styles, and some of those are affiliative, self-enhancing, aggressive, and self-defeating. These are the big categories.

Certain types of these styles of humor in the workplace tend to make leaders more human. Unfortunately, certain types of humor also tend to denigrate and destroy people. So it’s not just about being funny. If we want to talk about these kinds of social benefits of humor, it’s about being funny in the right ways. Accordingly, I try to make the risks very, very clear to my students because we’ve all been around very aggressively funny people, and it’s terrifying. It can be really destructive.

5) You also teach about various humor frameworks to help better understand why things might be funny (or not). What are one or two things everyone should know about how to be better at bringing humor into the workplace?

One common misconception people have about humor is that people are either just funny or not, and then that’s the end of the story. That is not true. Humor is a skill like any other skill. Just like some people are naturally gifted musicians, and some people have trouble carrying a note. This is true of humor, too. Anyone can get better at music. You may never be a virtuoso, but anyone can take some lessons and learn how to play “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” on the piano. Music can absolutely be learned. In a similar vein, the reason that I teach these theories of humor is to broaden people’s minds and make them realize that there are actually things that are funny. And, if we can identify those things that are funny, we can start to incorporate them into our day.

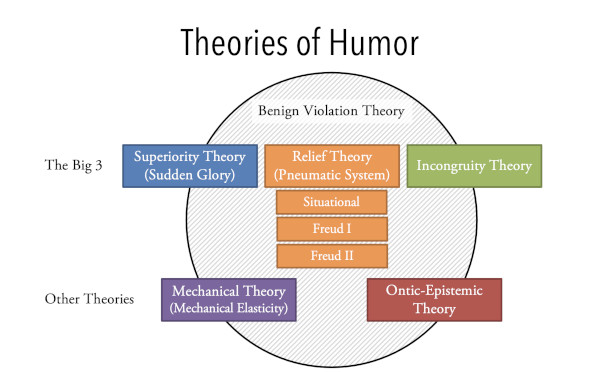

There are a whole bunch of theories out there. In the course, I overview a lot of them. But there are a few that are the big theories.

One is called Superiority Theory, which is that we find things funny when others are brought low. Things like physical humor, for example, if you ever watched Tom and Jerry cartoons where everybody’s getting beat up, and you found that funny. It can be dark—things like racist jokes, sexist jokes, etc.

Another is Relief Theory, which is where things get awkward, and then we resolve them. This can work in workplace settings. But a less risky type of humor is Incongruity Theory. This is where I say something just a little outside what you expected. Then I bring it back in. A lot of puns work this way.

The newest theory of humor that I’m aware of is called Benign Violation Theory. It is really become popular in the last decade or two. The basic idea is that humor arises as the result of some kind of violation. So, it could be a moral violation; it could be a linguistic norms violation, or a violation of expectations. There’s a violation, but the violation ultimately ends up being benign, so it’s not threatening. It can be illustrated by a famous quote about humor from Mel Brooks, who said, “Tragedy is when I cut my finger, comedy is when you fall into an open sewer and die.”

The idea here is if the joke feels threatening, it’s probably not funny. However, if it’s not threatening, and the violation is benign, it can be funny. So the advice based off of all of this is, if you want to be funnier in the workplace, look for these opportunities for incongruity. Look for things where you can point out weird things that are happening, or phrase things in a way that is unexpected. I find that exaggerations that are just slightly beyond what is believable tend to be an easy source of humor. For example, if you say you are stuck in traffic for a million years, that’s not really funny. But instead, if you said you were stuck in traffic for forever this morning, and somebody’s like, “Oh, how long were you stuck?” And your reply was, “I was stuck in traffic for nine and a half months.” It’s when it’s just slightly outside where people have to pause for a second and go, “Wait, no, no, no, you what?” There is an incongruity there—but it has to be benign.

The takeaway is that we can’t violate people’s expectations, norms, or preferences in a way that they ultimately find threatening. The problem is that a threat varies by context. If you’re hanging out with your buddies that you’ve known forever, you might have the kind of relationship where you can say really mean things and get away with it. It’s accepted as benign because there’s no question as to the fact that it’s not intended to hurt. Whereas you can say something that’s relatively mild to a new acquaintance, and if it’s interpreted as not benign, and it is interpreted in a threatening manner, that won’t be alright. It’s important to understand what is acceptable and what is not. In my opinion, unless you’re a professional comedian (and sometimes even if you are), it is your responsibility as the joke teller to make sure it’s benign, right? If we are trying to be funny and we end up telling people, “You need to loosen up.” No, that was on you, you should have read the room, and it is up to you as the joke teller to make sure that the joke is benign based on the situation you find yourself in.